Dateline: 8 August 2013

|

| This photograph, by Richard W. Brown, accompanies "The Pumpkin Watcher" in the October 1980 issue of Blair & Ketchum's Country Journal magazine |

Today's blog post is something different and special. It came about after I bought 21 old issues of Blair & Ketchum's Country Journal magazine yesterday at the Steam Pageant flea market in Canandaigua, N.Y. (I wrote about it HERE). I started looking through the old magazines and realized many of the articles were a great resource for agrarian-minded people. But, sadly, the magazine has been out of print for many years.

I went to the internet to see if I could find any archives or articles from the now defunct Country Journal, and there is practically nothing, though I did find the obituary for Richard M. Ketchum, who owned and edited the magazine back in it's day.

It's a shame that the information, and inspiration in those old magazine issues are no longer available, and that situation got me thinking about re-publishing some of the articles to the internet.

One article I came across and felt was well worth reprinting is "The Pumpkin Watcher," by Castle W. Freeman, Jr., in the October 1980 issue of the magazine.

Mr. Freeman's article touches on themes that are, or should be, important to rural people looking to be more self-reliant, (especially as we head into the probable collapse of western civilization). Besides that, the man is clearly a polished writer, and it is always a pleasure to read something that is well-written.

When the idea of re-publishing this article came to me, I did a Google search for Mr. Freeman and found His Web Site. I sent an e-mail, asking permission to republish The Pumpkin Watcher here. Permission came quickly and I had my son type it out for me this afternoon.

We all tend to breeze through what people have written on their blogs, but I encourage you to take a few extra minutes to absorb and enjoy this excellently-written and thought-provoking perspective on growing pumpkins...and so much more.

.

####

The Pumpkin Watcher

by: Castle W. Freeman, Jr.

What do we garden toward? A neighbor of mine shakes two hundred pounds of potatoes out of her garden in September. She has said, in disdain at another neighbor whose orderly, middle-size garden is given to lettuce, peas cucumbers, each in a half-dozen varieties, “He’s a salad gardener. He might as well be growing zinnias and petunias.”

There are salad gardeners and cellar gardeners, it seems—optimists and pessimists—gardeners who are thinking about July and gardeners who are thinking about February. Which are you? Which am I?

I’m a salad gardener with promptings toward the sterner, later crops that lie closer to the earth. I have my potatoes, keeping squash, and roots, but never in sufficient quantity to get me much past the winter solstice—if I cellared them, which I too often fail to do.

I grow pumpkins, too, though I grow them more to look at than to eat. Pumpkins aren't much good, really. Still, they are my favorite thing in the garden. They answer to some idea that we have of home’s abundance from the land. I plant them in their hills, and keep a special watch as they appear, spring up, spread, flower, bear, and grow. Pumpkins are the most nearly animals of the garden vegetables; watching over their progress through a season is like watching a calf come along. At the end of the day, when I get home from work, I grab a child if any is around and we head up to the garden for an inspection.

Our garden is narrow, laid out on a hill. The pumpkins are at the uphill end. This arrangement is intended to keep the pumpkins from taking over the garden. It has the consequence that our tour of the garden ends each evening in the pumpkin patch.

There we spend the cocktail hour in pumpkin watching. In July, when the fruit has begun, we poke around in the patch for the unripe pumpkins. They are well hidden. I never discover one without a little surprise on making out the dappled, rounded flank lying in the shadows like a pike at the bottom of a green pool.

I wouldn’t be without pumpkins in my garden, but few of my neighbors will suffer them in theirs. Those who do plant pumpkins do so apologetically; they put in a hill to have a couple of pumpkins for pies and a couple more for the kids at halloween. My own extensive and unruly pumpkin patch is a tip-off that in gardening I am a trifler.

Practical gardeners dismiss the pumpkin. They see it as a Texas longhorn among vegetables—an anachronism, unsuitable from every point of view that values efficiency or real productivity. Growing pumpkins for food, the serious gardener objects, is like raising elephants for meat: there’s a lot of meat there, all right, but how good and at what cost?

Pumpkins are a fair source of Vitamin A; otherwise they are nutritionally nothing special. The pumpkin’s vines and leaves take up a great deal of space in the garden that could better be given to other crops. Therefore, if you calculate the ratio of space required to usable food harvested, pumpkins are unproductive. Furthermore, the dark recesses of the pumpkin patch, beneath the profuse and closely growing vines, harbor all manner of mice, snails, slugs, and worse.

And anyway, how many pumpkins can one gardening family find use for: one? three? six? Like every pumpkin gardener, I wind up with eighteen or twenty when I can use maybe four. I could keep the excess in a root cellar. I don’t. They rot on the ground. I could feed the excess to goats or pigs. I have neither, want neither. Altogether I’d do better to procure pumpkins for use in season at a roadside stand. My friends and neighbors have pointed this out to me. They are cellar gardeners, expert and dedicated. For them gardening may be fun, but it’s no game. They aim to take from their gardens some important part of the food their families will eat during the course of a year, and so get around the nation’s food producing and marketing system, which, in their view, is organized to deliver bad food at high prices. From that system their gardens give them a degree of independence.

Independence is what my neighbors are gardening toward. They look backward to a time when rural America was mostly a land of small, self-sufficient farms. In Vermont, where I live, those times are by no means remote antiquity. Down to the turn of the twentieth century in much of this country plenty of people lived on small or middle sized farms that produced everything anybody on them wanted except for salt, pepper, and a few other odd spices.

These old farmers lived completely the kind of independence that today’s cellar gardeners seek to approach. Furthermore, I suspect that in some cases they did so in much the spirit as that in which my neighbors today garden. That is, the old farmers grew their own potatoes—latterly, anyways—not because they couldn’t get potatoes at market, but only of cussedness. They were damned if they’d pay a dime for a potato at a store when they could grow a better one for nothing.

My cellar-gardening neighbors honor the independent farmers of our great-grandparents’ time, and there are resemblances between them. But there are contrasts, too, and one of them has to do with pumpkins.

In one of the towns of northern Vermont there is a Pumpkin Hill. The story of the name is that at the time of the region’s earliest settlement the community survived a hard winter by eating pumpkins after a plague of grasshoppers had destroyed all the other crops. Another version has it that the grasshoppers destroyed all the crops, pumpkins included, of the settlers who lived at the foot of the hill. Crops on higher ground were spared. Settlers rolled surplus pumpkins down the hill to their unfortunate neighbors below, and so everyone got through.

The point of the story for my purposes is that Pumpkin Hill got its name in a time and place that had plenty of use for pumpkins. The implication of Pumpkin Hill is that the old Pumpkin Hillers—self-sufficient farmers like those whom my neighbors admire—had a good place for pumpkins. Yet my neighbors won’t touch them because they aren’t practical. Evidently there are different ideas of what’s practical at work here.

Different ideas about things are also behind another contrast between the independent gardeners of our day and those of generations past. We have different ideas about independence itself, and about community. The differences, for some reason, come to me most forcibly at harvest time.

I have a picture of the harvest of the old Pumpkin Hillers. It’s October, after the frosts. The prostrate vines are a dead tangle, the pumpkins ripe and hardened off. Today they are to gathered in. A gang of men and kids—family, neighbors—bring a farm wagon up from the house. Together, they go among the dry remnants of the patch, cut the pumpkins, lug them to the wagon by the score. Everybody pitches in. They load the wagon, then creak back down the hill. Perhaps they waste one or two pumpkins by rolling them down, in a ceremonial re-enactment of the legendary season when their forebears supposedly supplied the bottom settlements in the same way.

In my garden these days the harvest proceeds differently. My harvest is solitary. My neighbors don’t help out, except by advising me not to plant so many worthless pumpkins next year. They are gathering in their own gardens. I don’t help them, either. We are every man for himself. We want it that way, I guess.

By contrast, the old Pumpkin Hillers, who do rely on their own gardens and fields for food, had no idea of being individually independent. In their isolated settlements they were self-sufficient collectively; but families or households in the same settlements were very far from being independent severally, as we are. They were bound up with one another, dependent on one another, in ways and to degrees that we must find hard to imagine, and that we would be reluctant to accept for ourselves. If the men were haying over at Jones’s on Friday, you went to Jones’s and hayed, too. It didn’t matter that you had important work unfinished around your own place, or that you felt sick or out of sorts, or that you didn’t like Jones or he you. You helped Jones hay, or maybe when it came time to make your hay Jones wouldn’t help you.

We don’t want this kind of life. It sacrifices privacy. It implies a regimentation that we find repugnant. Also, I think, we don’t quite believe in it. We would rather rely, for example, on the oil dealer and his employees for our winter’s heat than on the collective labor of our neighbors and ourselves freely contributed, as in a firewood bee. We distrust complicated obligations. Our obligation to the oil dealer is a simple statement of account: cash for goods and service. Our debt to our neighbors for their help would be harder to define, and harder to discharge. And then, if the oil dealer fails us for any reason, we can buy from his competitor; if our neighbors fail us, we have no remedy.

Still, some of us seek a measure of independence through our gardens. The hitch is that we have independence confused with individualism. We think that each man must make it on his own, bail his own boat. We all believe this. But if times should ever really become hard, and our self-sufficiency be put to the test, it will fail for its insistence on the separate, isolated individual as the only possible unit of salvation. Then there will be much work to be done, and we will need to learn to get it done together.

It may never come to that, of course—probably won’t, or anyways not all at once. For my part I hope it doesn’t. Any hypothesis on which the individual American was suddenly obliged to grow his own food—all of it—or rely on his near neighbors to grow it is a hypothesis on which scores of millions, in America and elsewhere, would perish in a year’s time. I would be one of them, without a doubt. I’m a salad gardener and a pumpkin watcher, as I’ve said, not a pumpkin harvester. It’s a harmless, solitary pursuit. I wouldn’t want the whole town up in the patch with me on one of those bright October days when the great ripe globes, like expiring suns, lie among the wreckage of another garden year.

|

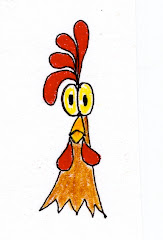

| Front cover of the October, 1980 issue of Blair & Ketchum's Country Journal |

6 comments:

That is thought provoking. It causes an examination of motives almost. I've often imagined a community like the author describes, an independent community of folks that rely on each other. It brings to mind a situation here: I have this wonderful neighbor who plows me out after snows every winter. Been doing it for years. He has to go to work pretty early in the morn, so he'll be out there at 2am plowing my driveway. I've never asked him to do it and he won't take my money, and it bothers me: how will I ever pay him back, I asks myself. Well this summer he has been extremely occupied with other things and I've been able to sneak in some stealthy lawn mowings. I love the payback! Anyway I often contemplate my own stubborn extreme independence, it's borderline selfishness perhaps. Thanks for posting that article, I recognize the cover of that issue. I was 20 years old back then and was beginning to embrace that spirit of living off the land. By the way, I planted a 50' row of New England Sugar Pie this year. They are perfect little pumpkins.

Mick

Mick—

Your comment focuses on one of the two themes in the article that I wanted to present to readers here. I appreciate your story and thoughts. I was 22 in 1980 and never subscribed to Country Journal magazine, but my father-in-law did and I am also familiar with many of the covers in the pile of magazines I bought.

Sharing the magazine articles and pictures is greatly appreciated. Community will become very important in the near future. That is going to be a huge culture shock for people... and a learning experience that may not be quick or easy to come by.

Shannon

Herrick -

Thank you for printing this. Reminds me that we truly don't live our lives simply for ourselves.

I was also 20 years old when that issue came out. Dreaming of the farm I wanted and of living off the land. My parents had sold their farm and moved to South Florida 2 years before I was born. All I got to have were the stories. I still live in Florida, at least now in North Florida where there is a little less pavement. Still in the city limits, but I have my chickens, ducks, turkeys, rabbits, and quail in the back, as well as my garden and fruit trees. My pumpkins didn't make it this year--vine borers got them!

I did live in a rural area near here for awhile, but I was renting. I had a few friends that I considered community, but not any of my neighbors. I would load up the kids and run to milk one's goats when she couldn't get home in time. Or go chase down another's hogs when she was at work and got a call that they were out. I was the strange one then, I homeschooled so I was home to be called on in emergencies. But here I haven't found that sort of community. I've been here 13 years and no one else around here does the 'crazy' things I do. This year I will begin homeschooling my grandchildren, and hopefully, we can find some sort of community. It is nice, though, to have 3 generations in the home. Kind of like the old days!!!

Debbie

I used to subscribe to Country Journal. What a great magazine it was, and I missed it when they quit printing it. I loved the middle insert that had the How to's. I wish there was another to take its place. Thanks for the return to the past.

Post a Comment