**********

We arrived at Monticello early in the morning. The home, which Jefferson designed, started to build when he was 26 years old, and worked on the rest of his 83 years, is an architectural treasure. It is on the top of a mountain. The word, “Monticello,” means “little mountain.”. The whole place is a testament to Jefferson’s talent, and his creativity.

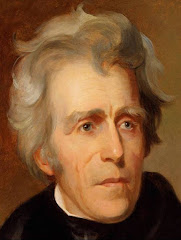

Our tour of the house was a delight. I knew almost nothing of Jefferson’s family prior to the tour. But I found myself drawn to the story of his daughter, Martha Washington Jefferson. Our tour guide pointed to a large painting of Martha and explained that she was one of two daughters born to Jefferson and his wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson. Martha, the daughter, was known as Patsy.

Jefferson and Martha actually had six children but only two survived to adulthood. She died after giving birth to the sixth child. Martha and Thomas Jefferson had been married only ten years. He was heartbroken and despondent for a long time after her death, and he never remarried. Patsy’s younger sister, Polly, died at 25 years of age after giving birth to her second child.

What attracted me to Patsy was the fact that she had 11 children, home-schooled them, and her home was Monticello. She also served as her father’s First Lady when he was president of the U.S.

Where was Patsy’s husband? Well, according to our tour guide, Patsy was married to Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr., a Virginia planter and one-time governor of the state, but she was entirely devoted to her father.

Imagine for a moment, Thomas Jefferson, the grandfather, surrounded by his eleven grandchildren, all living in the same home. Our tour guide told us that other family members were frequently there too. It was a very busy household!

Thomas Jefferson retired from public service to Monticello, where, for the next 17 years, he was active in farming, gardening, scientific observation, and so much more. But he was also very involved in the lives of his grandchildren. From what little I’ve read on the subject, his grandchildren had the fondest memories of growing up at Monticello and of their grandfather’s influence in their lives. That is, to me, a very endearing picture.

In Jefferson’s library, the tour guide pointed out several pieces in the room, including a walnut and mahogany “seed press,” that was probably made by the slave, John Hemmings.

That was all that was said and it begged the question (I tend to ask a lot of questions of tour guides): “What is a seed press?” It turns out that “press” is an 18th century word for an upright cabinet or case used for storing objects. For example, Jefferson would not have called a bookcase a bookcase; he would have called it a book press.

And so Jefferson's seed press was a cabinet where he stored glass vials with specimens of the many garden seeds that he collected and planted each year in his gardens. He kept his vegetable and flower seeds right there in his library. They were important to him.

That cabinet intrigued me. As the rest of our tour group filed out of the room and into the next, I lingered and visually studied the press. Though we had been forbidden to touch anything in the home prior to entering, I was tempted to open the door for a little peek inside (but I didn’t).

What surprised me about Jefferson’s seed press is that, compared to much of the rest of the furniture in the house, it was very primitive. It was, in fact, a classic example of Yeoman Furniture (without milk paint). I’d like to have measured drawings of the cabinet and make a reproduction.

Our tour of the house was much too short but that was, I suppose, necessary considering the crowds of people who show up to see Monticello. Pictures in the house are not allowed, but I took these pictures of the kitchen, which is in a basement setting (that was typical for plantation kitchens of the time). Something like this kitchen would make a great summer kitchen on any busy modern homestead.

Our next stop was a tour of the gardens. Jefferson’s vegetable or "kitchen garden" was a 1,000-foot-long, two-acre piece of land terraced into the mountainside, just south of the house. Here are a couple of garden pictures:

To the left in those pictures and out of view is a stone wall which retains the terraced land, allowing for a large, level area on the slope of the mountain. Below the wall, Jefferson had an eight-acre orchard (300 trees), two vineyards, and plots of figs, currants, gooseberries, and raspberries.

Preservationists know the what, where, and how of Jefferson’s gardens because he kept copious records. He was into it.

In 1793 Patsy wrote her father complaining of insect damage in the garden. His response is insightful:

”We will try this winter to cover our garden with a heavy coating of manure. When earth is rich it bids defiance to droughts, yields in abundance, and of the best quality. I suspect that the insects which have harassed you have been encouraged by the lean state of the soil. We will attack them another year with joint efforts.”

In the background of the above pictures you can see a taller mountain. That was once a part of Jefferson’s plantation and he called it Mount Alto. In recent years, the Monticello foundation purchased 300 acres on the top of the mountain. They plan to reforest the cleared area so the view will be as it was in Jefferson’s day.

Our tour guide told us that the Foundation paid 15 million for the Mount Alto property. That amounts to $50,000 an acre. Coincidentally, it was Jefferson as President who paid 15 million to Napoleon Bonaparte for the Louisiana Purchase. That purportedly calculated out to three cents an acre.

There is much more I could say about Jefferson and Monticello, but this is rambling on. I will post one more blog about Jefferson and tell you about the significant financial crisis he and his family faced later in his life. There are lessons that we today can extrapolate for ourselves from the story.

===============

To read the next essay in this series, Click Here: The Story of Thomas Jefferson's Personal Debt

===============

3 comments:

Oh I hope you'll ask the museum if you could the measurements to craft a reproduction seed press!...They might be open to that approach...they could sell your plans in their museum store!

Your blogs are most educational - thank you for writing!

There is a website that has a photo and the overall dimensions of the seed press:

http://explorer.monticello.org/index.html?s1=1|s3=59|tp=1

Excellent post. We are considering visiting Monticello and I have been fighting over my opinion of Jefferson, as to who the man really was. I agree, his daughter Patsy is fascinating. I tried to find some books about her and wasn't able to... Maybe at the visitor's center they'll have some :)

Post a Comment