Dateline: 30 September 2014

|

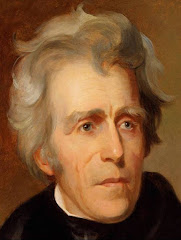

| Photo by Paul Cyr (click to see enlarged view) |

My Aunt Carolyn recently sent me the picture above. It shows my maternal grandfather's farm, on Forest Avenue Road in Fort Fairfield, Maine, as it looks today.

I sent the picture to a cousin and he wondered if I might be mistaken. That's because the old place looks a whole lot different than it once did. The red barn with silos was never there before. Neither was the long back addition on the white house, nor all the other outbuildings and additions. There was only the house and the red-roofed barn in the foreground.

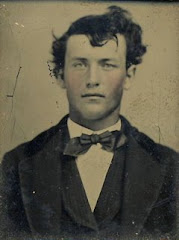

|

| The barn on the right was the only barn on the farm when my grandparents owned it. I remember the barn very well. (photo by Paul Philbrick) |

My grandfather died in 1971. My grandmother sold the farm a few years later. It changed hands several times before an Amish family (the Yoder family) from northern New York state bought the place and moved in back in the summer of 2007.

Near as I can determine, Noah and Lovina Yoder, along with their 11 children, were the first Amish family to settle in Aroostook County, Maine. Noah is a farmer and a carpenter. He builds barns and furniture. I'm pretty sure all the buildings and additions to buildings on the farm have been made since the Yoders arrived. It is great to see.

This DownEast magazine article, featuring Noah Yoder's story and that of the Amish in Northern Maine, is particularly good. The picture at the top of the article of the Amish boy making a snowman shows a little bit of my grandfather's barn. Sadly, the article reveals that Noah's 22-year-old son was killed in an auto accident one winter. He was a passenger.

This Web Page shows pictures of an Amish barn raising in Easton, Maine, which is right next to Fort Fairfield. If you look closely you'll see that the barn is not a traditional post and beam structure. It turns out the Amish rarely, if ever, put up post and beam barns anymore.

These days, Amish barns are nailed together using 2x6 lumber. You can learn more about the specifics of how Amish barns are made in Maine from This Link.

I have a lot of memories of my grandfather's barn. Back in the July issue of my 2010 Deliberate Agrarian Blogazine I told the story of helping him repair potato barrels, and getting split ash hoops from the indians, and nearly blowing my hand off with a firecracker I found in the barn. Click on that link and you will also see a picture of my grandparents back in the day (there's a picture of me too, back when my memories were fresh and real and lodged themselves into my brain).

The barn was built by my Uncle Clyde Kennedy (author of The Hard Surface Road: A Memoir of the Great Depression) after WW2. Clyde married my mother's sister, Aunt Dawn. The lower half of the barn is a potato cellar. If I remember correctly, the upper floor of the barn is concrete (it would be the ceiling of the potato cellar). I'm pretty sure this is right because I recall there was a rectangular concrete hatch in the floor. Maybe more than one. I think they were there to unload harvested potatoes through.

Anyway, there is a little bit of a secret in that barn. One of the concrete hatch covers has my grandfather's name in it: P.O. Philbrick. The letters were written in wet concrete by Uncle Clyde, and there is also a profile drawing on the hatch (made in wet concrete) of my grandfather's head. Uncle Clyde was an artist and I was always amazed as a kid by the excellent likeness of my grandfather.

If I ever make it back to Fort Fairfield I would like to stop and see if that little secret is still in the barn.

#####

You can see a film clip showing the beautiful farm country of Northern Maine (including my grandparent's farm) from an aircraft in This YouTube Movie. It also shows some Amish boys plowing fields with horse teams.

|

| My grandparent's house looks pretty much the same on the outside (photo by Paul Philbrick, December 2013 |