Dateline: 4 April 2016

(Click Here to read Part 5 of this series)

|

| click picture for larger view |

This is a continuing series, highlighting some quotes from Oliver Edwin Baker, as found in the 1939 book, Agriculture in Modern Life.

###

"Five years ago I attended a conference of agricultural economists in Germany, and for a week before and a week after the conference the German hosts arranged for a few members of the conference to visit about 100 German farms, mostly "Bauern" or peasant farms. My idea of the European peasant and his farm was greatly changed by this visit.

I found the farmer, or "Bauer," a man proud of his ancestors, proud to be a farmer, and one who generally possessed a sense of superiority over city people.

Although in many instances the house was built by the farmer's father or grandfather or great-grandfather, it was built of brick, had a tile roof, the hall and kitchen floor were generally also of tile, and nearly every house had electric light.

The typical bauer farm is 40 to 100 acres in size, but it produces as much as a 100 to 200 acre farm in most of the United States. The barns are generally much better built than in our country..."

At each farm the visitors were provided with a page or two of mimeographed information about the farm. Most of the mimeographed sheet told of the acreage of the crops, yield per acre, fertilizer used, crop rotations, number of horses, total cattle, milk cows, swine, chickens, etc.; but always at the top of the page for those farms which could claim the honor, and many of them could,was a statement somewhat as follows: "This farm has been in the family 200 years." Some farms had been in the family for 400 years, some 500 years. One farm had been in the family sine the 11th century. As we considered what had happened during these centuries, wars, economic crisis, periods of inflation and deflation, political revolutions, the thought came to us— How long ago would this family have lost its wealth had it been invested in anything else than land?"

###

"This concept of the farm as the hereditary home of the family has profound consequences. We saw practically no soil erosion in Germany, except in the vineyards on the steep slopes of the Rhine Valley. This absence of erosion is owing partly to the cool summer climate, with few torrential rains, partly to the crops grown, but partly also, and perhaps primarily, to the conviction that the land is the foundation of the family, the heritage from the past to be handed on to the next generation undiminished in fertility, and, if possible, with its productivity increased. One could sense among the German farmers the feeling that a man who lets his land erode away was not only dishonoring his ancestors but also depriving his son of the proper heritage. He is conserving both the natural and the human resources."

###

"The German farmer, when old age draws nigh, does not retire to the county seat, as many farmers in our corn and dairy belts did before the depression, and build a house that represents the savings of a lifetime, renting the farm to a tenant. Instead the "Vater" and the "Mutter" retire to a portion of the farmhouse... and a partnership agreement is entered into with the son, who, with his family, occupies the remainder of the house. Sometimes a new house is built for the old folks or for the son. This son, who later inherits the farm, does not spend most of his life, nor dies his wife, digging and delving and saving to pay off the mortgage on the farm; but in much of Germany he starts without debt, in a house that is usually built of brick, with a tile roof, and his savings are in turn used to improve the farm and educate the children. The money that the German farmer makes in good times is mostly plowed back into the land, so to speak; a new house or barn is built, or a piece of land is drained, or better stock bought. Each generation climbs from the shoulders of the preceding generation, and wealth and culture accumulate, instead of being dissipated by migration to the cities."

###

"The young man who starts operating a farm in the United States today, unless he inherits it, generally has a harder task before him in acquiring wealth than many pioneer farmers of years ago on the frontier, for he starts with a load of debt. If the youth on the farms could start life free from debt, which is particularly heavy in agriculture because of the high ratio of investment to income, the farmers of the Corn Belt and the southern counties of the Great Lakes states, and in some of the best counties of the East and South and West, within two or three generations might reach a level of culture and comfort such as the world has never known. For no other nation in the world has so extensive an area of fertile soil, and so large a proportion of level or gently rolling land adapted to the use of machinery, with the possible exception of Soviet Russia, climatic condition so favorable to the most productive feed crops, corn and alfalfa, and a market of nearly 100,000,000 non-farm people with no tariff barriers between producer and consumer."

###

"Nature has provided in the Corn Belt and the southern portions of the Great Lakes states, in many of the valleys and plains of the eastern and far western states, also in certain portions of the south, the basis for as fine a rural yeomanry as the world has ever known, but instead it is becoming a land of tenant farmers or heavily mortgaged owners living in houses many of which are little better than hovels."

###

10 comments:

I don't know about anyone else, but I would love to be a peasant farmer!!! I wonder what it is like today, eighty years later? Are all those Bauern farms still in the same families

and actively productive?

One thing I saw out in Colorado, around Steamboat Springs, to be exact, was large ranches with aging farmers. The adult children mostly moved away because the ranches couldn't support more than one family (in their minds and with today's consumer minded mentality). They might carve out a small piece of land to put up a trailer home but would be hounded by high taxes due to the ski resort's presence. No working class person could afford a simple home within 30-40 miles of Steamboat. They couldn't sell the mobile home when they couldn't keep up with the taxes but a rich person would buy it, trash the trailer, putting up a McMansion...further driving up taxes. Now the ranches were worth money because of the amount of land and the children were gone so the ranch was sold to rich folk as second homes and ranching stopped or greatly curtailed. So much for the heritage of western ranching.

In Ireland, it was the custom to divide the land among the boys...which ended up after a few generations, making farms of one acre, barely subsistence farming. This was one factor in the Great Famine, or so I've read.

Interesting series Mr. Kimball. Thanks for sharing.

Pam

Pam—

I wondered the same thing about the farms. My guess is that the bauern farms are not what they once were. OE Baker wrote for this book probably in 1938, and he said he had visited Germany 5 years earlier. So it would appear that the peasant farms survived WW1, but I'm thinking that WW2 and the rise of industrial agriculture had a devastating impact on that way of life.

I did do a little Google searching and found This Link that told about the Nazi effort to preserve these family farms. Interesting.

Pam—

Good observation about the aging farmers and their ranches not being able to support the children in farming. O.E. Baker actually writes quite a bit about that exact problem. It is a great concern to him, but he is pretty much at a loss to offer a good solution to the problem. His story about the German farmers is offered as an ideal example, in contrast to the crisis he saw happening in America.

He explains that the American farmer's children would go to the cities for work opportunities and became established in their urban life and careers. They would go to the city because there were limited opportunities on their parent's farm or in the rural communities. Then, when the parents died (while on the farm) the children would inherit and rent the farm out to a tenement farmer, or sell and divide the money. The farms would often be purchased by city people, who had the money to pay a high price. Other farmers in the community, or aspiring farmers, wouldn't have the money to afford the high prices of land.

Or, one son would follow his father in farming and take over the farm, but if he had siblings, he would have to borrow money to buy them out and hold onto the farm. Thus putting his future success at risk.

The problem with tenement farming, from O.E.'s perspective was that the farmers and their families were not secure on their land, AND tenement farmers rarely care for the land they rent like they would if it were their own.

It would appear that this problem has only gotten worse in our day, as once-productive small family farms have been sold to urbans who don't work them, or who rent them out, or the farms have been absorbed into enormous agribusiness "farms." I have seen it around here in my lifetime, and it is probably more of an issue where you live in VT. After all, a "summer home" in Vermont is the dream of many successful urban people in the Northeast. It's a good investment, right?

I'm sure that, within families that care about preserving a family farm, there are wise ways to pass the farm on to the next generation (I think Joel Salatin has written about this), but these are the exception to the rule. It's a sad situation.

If someone like O.E. Baker, with his knowledge of agriculture and "the numbers" couldn't offer a good solution to the problem, I don't know that there is a solution. It will have to play itself out.

Some further thoughts on the preceding...

At this point in time. I think the "solution" to the consolidation and loss of family farms is for agrarian-minded families to establish themselves on a small section of affordable land. It is still possible to buy a few rural acres for a reasonable price in many areas of the country.

If that is done by a lot of people, and those people make their small section of land productive, while generating the majority of their income from home-based cottage industries, we would have a resilient smallholder class. A new type of yeomanry. Not farmers but self-reliant homesteaders.

These homesteads could, in time, be developed with long-term goals and deliberately passed on to future generations in the family. A multi-generational smallholding instead of a farm.

I'm trying to figure out how best to do this. I think some sort of family land trust might be the answer. I know a family around me that has done this with 100 acres. I don't know anyone else who has done it, or even cares to do it. It would be land for some to live on, but for all to enjoy and utilize in productive ways if they so choose. If future generations have a secure spot of family land, they have a measure of security that a paper-and-digital financial inheritance can't offer.

This is just food for thought in the midst of the agrarian struggle.

One of the factors that prevent long term ownership of family farms is tax law. The transfer costs are huge. So unless some holding company type arrangement can be made, and legal, we face the issue of continuing to lose family farms.

Item of note -- The average age of farm owners is 62.

T.S—

I'm thinking an irrevocable trust will legally preserve and protect a property for generations. Not the more common revocable trust. No one in the family would own the land, but they could have use of it. And it is protected from liens & etc.

But I'm surmising at this point.

There is some discussion about protecting family land At This Permies Discussion.

I see that there are several online articles about Preserving a Family Vacation Home With a Trust

Seems like the same principle would hold true for any piece of land and real estate. The problem for me would be that of funding an endowment to handle maintenance expenses. That's way outside my socio-economic paradigm.

But there may be useful concepts that can be adapted for less prosperous families. It looks like a Limited Liability Family Partnership may be another way to go.

Too bad this sort of thing has to be so complicated. And expensive. :-(

Hi Herrick, Been reading these every day and I just continue to be overwhelmed with feelings of loss and despair for what my kids have, or rather don't have in their future. At one time back in the beginnings of the last century my family owned all of the abutting land surrounding the present "homestead" of about two acres! Homestead is how this piece is listed in the town tax records. There is NO possibility of buying back any of the land due to the ridiculous land prices, about $800K to a

$1M for an acre! I tell my guys to just hang on as best you can, always looking to the future with a prepper mentality. After all the fuel, electricity and food is gone, all those million dollar homes will make a fine supply of firewood for a few years! I have quite a supply of tools you would need to retrieve your wood supply for a winter. Saws, axes, files to keep them sharp. The list goes on and on. Great series. Just made 30 more shade discs to try with my parsnips, and other veggies.

My evening reading these days is rereading the Whizbang idea book! Happy planting. OBTW, this years three hogs arrive tomorrow! Best, Everett

I can't tell you how here in Vermont how many 50-100 acre properties sit empty most of the year after having been bought by non-residents who "modernize" the 1800's farmhouse and then let some of the pastures go back because the revere trees so highly. Then they sell off some of the land to other people who put up McMansions....its just disgusting. You would have a stroke if I told you what our taxes are on our new 66acre homestead. They are literaly 10x what we paid for the same size house in Colorado. Granted that was on 1/2 an acre. We have to pay a forester to develop a plan and put a majority of it into current use or agriculture and then grieve the taxes to our rinkydink town to get them to a reasonable amount. I would have to work at my hospital job for 2 1/2 months just to pay the taxes. But, it's rural, quiet and private. And no one can tell us what we can do with the land.

We've talked about what to do with it when one or both of us die as we had no children. We have one nephew and great nephew who we never see. Seems a shame we will put so much into this only to not have anyone to pass on a tradition to. But that is the plan God gave us and we must make the best of it. Maybe some one or thing will change before our time is up.

Och, I'm rambling.

Great postings and great comments by all.

Respectfully, Pam

Pam,

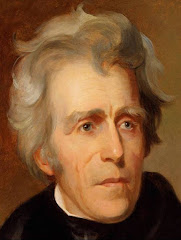

I suppose my own family is a part of this story. My grandfather left VT (Lincoln?)in his early 20s, and I have no idea what happened to the family home his mother grew up in. My dad, whose photo was taken as a young vacationing boy on the front porch of the farmhouse, has since passed away. I would love to know where the old homestead was and who owns it now, but really have no idea where to look. (It belonged to the Hanks family, and I believe they owned a sawmill as well....?) On the other side of my family was a 100-acre farm full of orchards in Plainview, MI. No telling what has happened to that, either.

Joel Salatin has some interesting ideas on passing the farm to the next generation (I think they are found in his book "Family Friendly Farming.") Basically, it entails a transfer of title while the older members of the family are still living. But a trust is a very interesting idea, too.

Post a Comment